As a SoCal math teacher, I obviously jumped on the opportunity to attend the National Council of Mathematics Teachers (NCTM) Annual Conference when it was in San Diego, CA in April of this year. It was everything I had hoped for, including a 6AM yoga session with a customized NCTM yoga mat. Because I only live a few counties over the travel was only a 2-3 hour drive away.

I had great company on that drive home, Matt Vaudrey and John Stevens. The two of them had presented at NCTM; I had the honor of co-presenting with Matt Vaudrey. After stopping for lunch and sharing some of the takeaways from the conference we started thinking about what we wanted to share with teachers next.

What came from that conversation inspired a keynote presentation for the Orange County Math Council’s (OCMC) Math Tech Night that John Stevens and I co-presented in October, and my workshop session at the California Mathematics Council (CMC) Southern Conference in November.

I’ve spent the last few years teaching what my school calls “Academy” classes. These are classes that are populated with students that typically struggle in math and would benefit from a class that offers more support and opportunity for success. So, that meant students that historically had lower grades in math and students that have an IEP or a 504 are typically offered this class as an option, as opposed to the regular, college prep, math class. We have Academy classes at the Integrated Math 1, 2, and 3 level. And so, my Integrated Math 2 Academy class is filled with students that did not identify as being a “Math Person” and many of them didn’t have great math class experiences in the past.

They’re already coming in feeling so defeated that I spend a lot of time building up their confidence and trying to change the little voice in their head that says they can’t do this. But along the way I began to notice that everyone kept telling me that math was just “too hard” for “these students”, meaning the students in special education, students with learning disabilities, students with historically lower grades…students with higher needs. And it wasn’t just a matter of the math was hard, what I kept hearing was that my students were just not capable, NOT ABLE to do this math, and that some of the math would be impossible for them to learn…SO DON’T EXPECT TOO MUCH.

I tried to challenge some of these comments with a more positive and hopeful attitude. I would say “I believe everyone can do math” I remember so clearly being told, “Well…actually, some of them literally, can’t.”

So, I started to think about how I could change this for my students and then for all students that have higher needs.

The first way we can give students with higher needs access to the math they deserve is to change the language that we use to talk to our students and how we talk about our students. We need to stop labeling them and remember they are students first.

When we think and speak about our students in a more positive light there’s something that changes inside of us. We start to remember they are people. That this student is someone’s baby. We become far more patient, kind, and compassionate. We’ll work a little harder and be more encouraging. We’ll be more willing to give grace and we all know everyone can use a little more grace.

And since our words are powerful, what we say TO students and what we say ABOUT students matter.

Some students need to be reassure that they BELONG. We can’t do that if we make them feel like they’re in the wrong class–like, they’re not good enough to be here or not smart enough to make it. They need to know they are a vital member of our classroom and that they add value no one else can. Our students struggle with anxiety and insecurities that we sometimes don’t even understand. The way we speak to our students can make the biggest difference. We can give students the strength and encouragement they need to push past whatever is holding them back so they can engage in the lesson and learn the math. Some students need to be shown RESPECT to be motivated to do well. They need to hear that they are valued, that their effort doesn’t go unnoticed, and that we respect them enough to meet them where they are.

We need to really see our students when they walk in the door…not their past mistakes or their disabilities…but each student’s potential to be the greatest student you ever have.

The next way that we suggest we can help students with higher needs access to the math they deserve is to keep high expectations.

So, when we use that negative language two things are in play: First, when we say a student “can’t” do math we start to think that it’s actually true. Second, our actions and educational choices start to convince our students that they should believe it’s true too. When we say a student “can’t”, we give ourselves permission to make things easier for them and we lower our expectations of them.

And I do believe we are trying to “help” or “support”. And even though our hearts might be in the right place we stop challenging our students and we rarely give them opportunities to rise to the occasion, In our efforts to help our students, our scaffolding turns into us reducing the rigor, lowering the DOK level, and making things easier for them. When we say students “can’t” we take the wind out of our students’ sails by convincing them that they can’t do hard things…like math. Let’s make sure that we are not part of the problem; that we are not subtly influencing our students and undermining their ability by lowering expectations in an effort to “help” them.

And the scary part is that this happens in the background; it’s subtle and so stealth. We’re not announcing, for all to hear, that a particular student isn’t capable, it’s a subtle influence in the way we speak and act towards students that have higher needs.

We had a really reflective and raw moment of clarity during my CMC session when I asked this question and asked teachers to share their responses:

The responses were powerful; what I realized is we needed a safe space to air out all our thoughts and feelings about what makes it challenging for us to teach students with higher needs. Teachers needed an opportunity to admit what makes it difficult without the fear of judgement; without the fear of appearing to not care or not have their students’ best interests at heart. We all needed the chance to let it go. And we did. And if you were at my session thank you for that moment. I encourage you to reflect and do the same.

So, with that said, we want to re-imagine what that support might look like. One way is making some intentional additions or enhancements to your instruction. Here’s a few ideas how to do that, and this is certainly not a comprehensive list, but a great start:

What I hear from teachers most often is that students with higher needs lack prerequisite math skills and sometimes even basic math skills like number sense. And what I hear most often from counselors and special education teachers is that students with higher needs take longer to process information and need extra time to let things sink in.

So, instead we decide we’re stuck and we spend time practicing the prerequisite skills or basic skills in class that we end up not having time to do any cool math activities; we reason that we just need to get them through the basics. Or worse, we don’t even feel like we have time to practice those skills so we just press on and hope they get something from each lesson. There is this constant tug of war between what we feel like we should do and what we would like to do.

First, start class with what the Classroom Chef’s called Appetizers. They’re essentially short activities that you do at the start of class to get them hungry for the lesson that is to come. Think about what an appetizer does to you at the start of the meal; it’s the same feeling we want to create for our students in our classes. Here’s a few favorites of mine that I use in my classes.

My students were different on the days I did an Appetizer. We started class more quickly and my students readily engaged in the lessons and activities I had planned for them. And because these activities give students multiple entry points, all students can feel success at them. One final solution wasn’t the goal; communicating and thinking about math was.

Also, this is the perfect opportunity to build in those basic skills that we are always looking to practice but never seem to find the time in our busy pacing guides. So, your students are struggling with percentages, throw in a Would You Rather? Math exercise. If you wish your students had more practice writing linear equations, use a Visual Pattern to do that! Or if you need your students to feel more comfortable speaking in class and sharing their ideas, try a Debate Math talking routine or a Which One Doesn’t Belong? exercise.

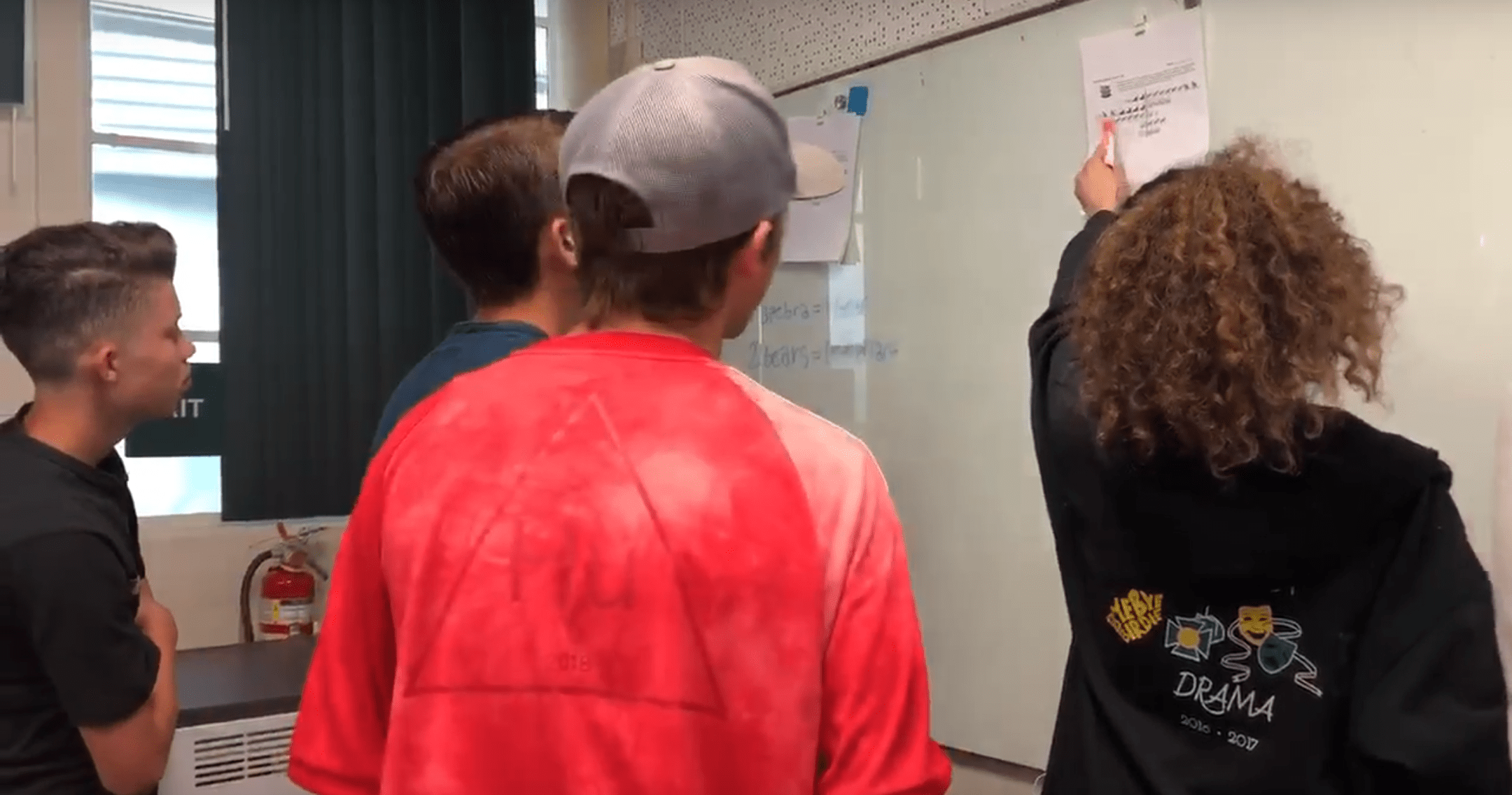

Second, get your students Up & Moving! Many student with higher needs need the physical reset of their bodies to stay focused and motivated to learn. Just a quick Google search on the benefits of movement will reveal to you how important it is to incorporate into any class, but especially classes that have students with higher needs.

Thanks for sharing this photo of your students using the Vertical Non Permanent Surfaces (VNPS) in your classroom, @ClaireVerti

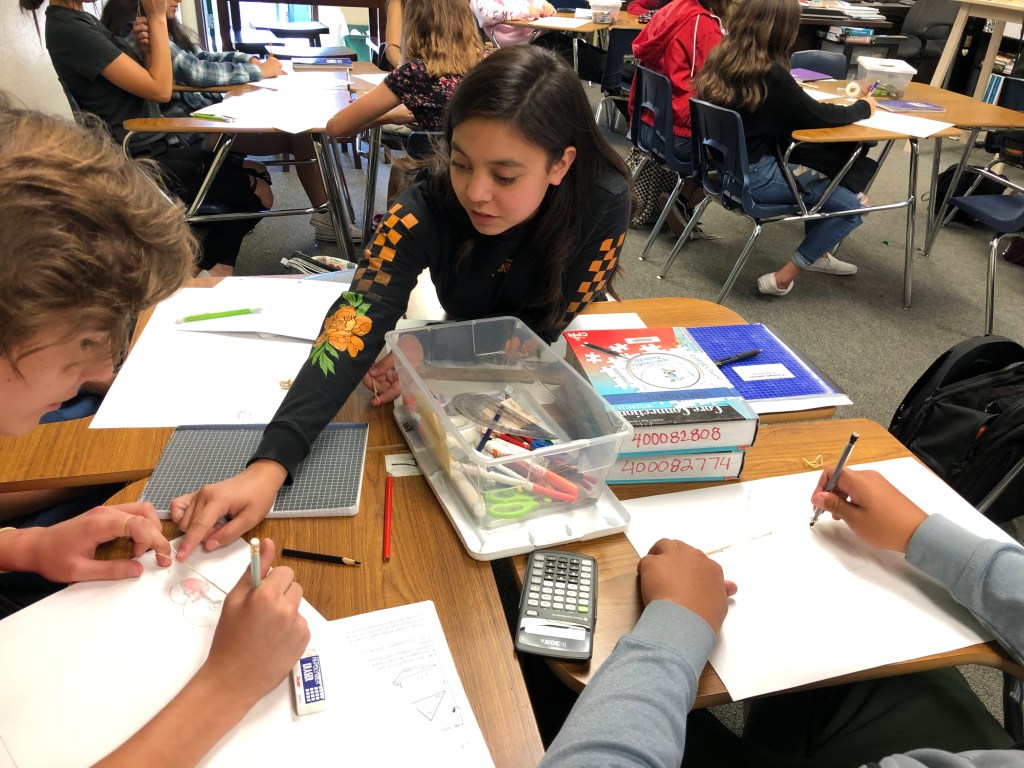

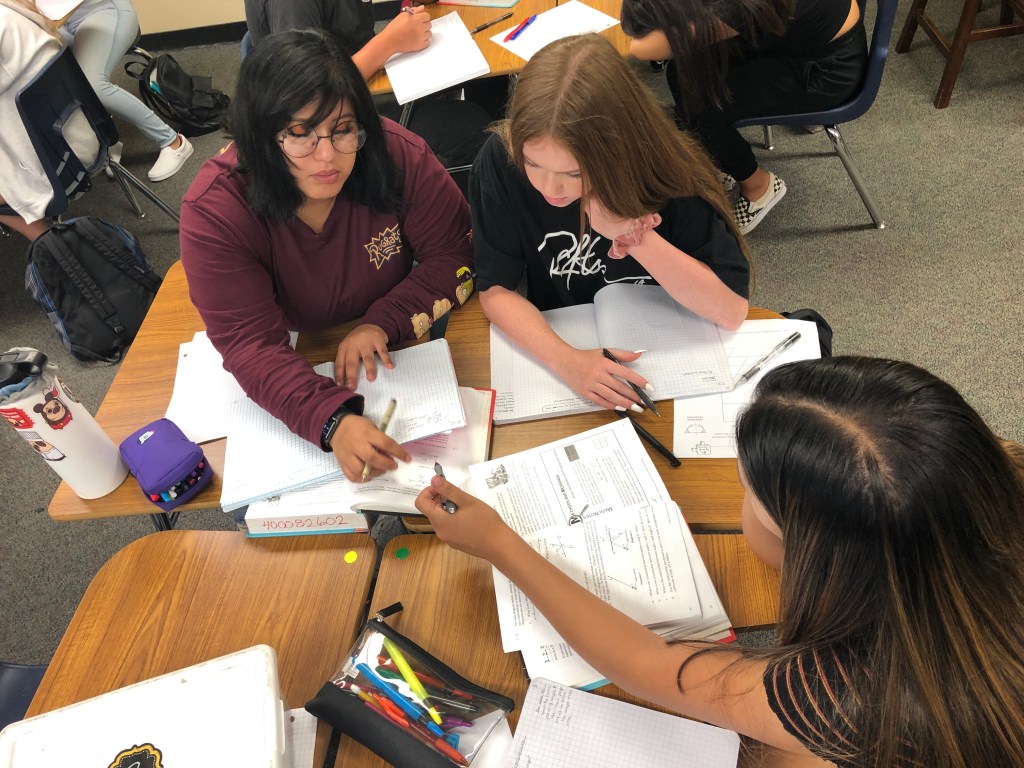

I have the pleasure of teaching math collaboratively thanks to the beautifully written educational program called College Preparatory Mathematics (CPM) and as a CPM Teacher Leader I have the opportunity to train other teachers amazing resources and skills to change classrooms into collaborative learning spaces. Their Study Team Teaching Strategies are collaborative learning structures and many of them involve the kind of movement I’m suggesting we use.

Here’s a list of some of my favorite strategies, collected from the CPM Educational Program and the Math Twitter Blogosphere (#MTBoS), that allows us to incorporate more movement into our lessons. Many of these don’t require a lot of prep work ahead of time and some can even be used on the fly when you notice your students dragging or starting to lose focus.

Third, use a Collaborative Closure activity to close the lesson. So often our students are engaged in an amazing lesson that we thought we planned so well just to discover that nothing stuck. Our students didn’t retain any information despite all our efforts to start with an appetizer and include movement. We have to give students an opportunity to reflect on what they learned each day and allow them a chance to articulate that for themselves.

And I know, I get it…we barely have time to do the lesson that asking for one more thing almost seems impossible. BUT…we also know that there are plenty of lessons we taught, and thought we taught well, that after assessing it was as if we never taught it at all! So, it’s worth the pinch of time to make sure we give students a chance to summarize what they learned in class in a quick and collaborative way. My challenge to us is STOP-DROP-CLOSE: the last 10 minutes of class, set a timer if you have to, STOP teaching, DROP what you’re doing, and CLOSE the lesson.

Here’s a list of my favorite ways to do a Quick & Collaborative Closure.

Changing the language, increasing our expectations, and enhancing our instruction are three ways we can begin to give students with higher needs access to the math they deserve.

I wonder how many students with higher needs you have in your classes? For me, it’s the majority of my students because of the way my classes have been populated. More than half of each of my classes are students with higher needs. I’m forced to adjust and differentiate instruction accordingly. But I know for most teachers there’s just a handful of students with higher needs. Many schools spread these students out among all the teachers in an effort to even out the load and share the responsibility. I’ve heard the term “balance the classes” used to describe this.

That all sounds fair and equitable until we start to think about a traditional classroom.

At the end of the grading period educators, from teachers to administrators, are accustomed to the “bell curve” or grades…this normal distribution. It is acceptable to us to have a handful of students that are not passing. We can’t win them all, right?

I wonder how many of those students that are not passing, that are struggling, are students with higher needs and have we done *enough* to make sure that they didn’t land there just because everyone expected it?

Let’s do all we can to give all students, especially those with higher needs, access to the math they *deserve*.

~PV