Oh, hey there! It’s been a minute since I last wrote and figured it was time to dust off this old blog and bring it back to life. The last couple of years have been a whirlwind of new adventures, challenges and successes. I’m excited to share the highlights with you!

You guys…I landed my dream job. I’m the Coordinator for Math Curriculum & Instruction in the largest district in Idaho: West Ada School District. I oversee all the math curriculum, resources, and instruction that takes place in kindergarten through 12th grade classrooms.

We serve just about 40,000 students and 2,100 teachers across 58 schools. The next largest district in our state is half our size. And because I know you’re numbers people, this equates to about 750 elementary teachers and 200 secondary math teachers that I have the honor of supporting.

As you can imagine, moving a system this large, instructionally, is a challenge. We often describe it as sailing a ship. We literally can’t change course quickly; it takes time, courage, patience, and a plan.

Thankfully, the captain of our ship is an inspirational instructional leader. Our superintendent, Dr. Derek Bub, is a visionary that is experienced, knowledgeable, and compassionate. His compass always points towards kids. He’s the same leader I wrote about in this blog many, many years ago. So, when I say I would follow him to the moon, I mean it. I admire that Dr. Bub listens with intention, draws his power from relationships, and encourages the people around him to dream big.

The Big Math Project

Within days of starting my new job Dr. Bub called me into his office and asked, “What if…” and began the conversation that would become our beloved West Ada Math Symposium. What I hope to share with you now is how we strengthened a culture of learning among the math teachers in our district through the Math Symposium.

We wanted to turn the ship. We wanted to provide consistent and impactful professional learning that would have a greater return on investment than, say, sending a few teachers to a conference. And we wanted to use our ESSER funds to invest in our teachers, not in things.

Then, we started to *dream*. We started to brainstorm the names of the most influential math educators that we have learned from over the years. Dr. Bub and I both came from Southern California where we were surrounded by brilliant math minds that would flock to Southern California for conferences such as NCTM and CMC-South.

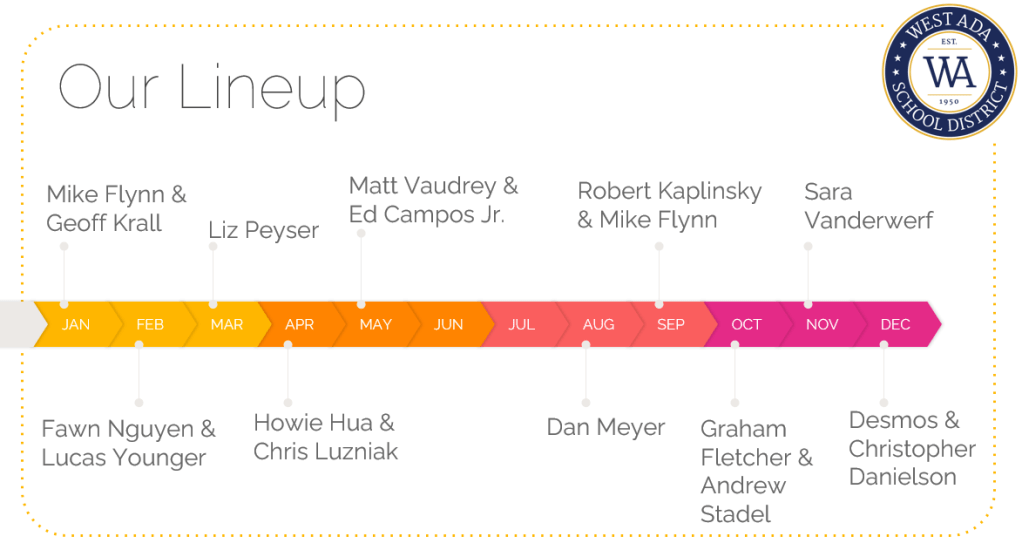

Robert Kaplinsky and Fawn Nguyen immediately came to mind. Dan Meyer, Sara Van der Werf, Howie Hua, Chris Luzniak, Geoff Krall, Mike Flynn, Graham Fletcher, Matt Vaudrey… Our list was not short. And for once, neither was our budget. It was the perfect storm to create something amazing: We had the vision, I had the connections, and we had the funding! We got to work and built the West Ada Math Symposium.

The Math Symposium

Our Math Symposium was a series of 10 full-day workshops, held on one Saturday per month, each featuring a different math educator. We initially invited only one teacher from each of our 58 schools to participate in the Math Symposium. Our original budget would only allow for this many but through the generosity of our Superintendent and our school board we were able to accept everyone who applied (96 teachers). We asked these teachers to commit to attending at least 9 out of the 10 Saturdays and we would honor their time with a $5,000 stipend, paid through ESSER funds, at the end of the series.

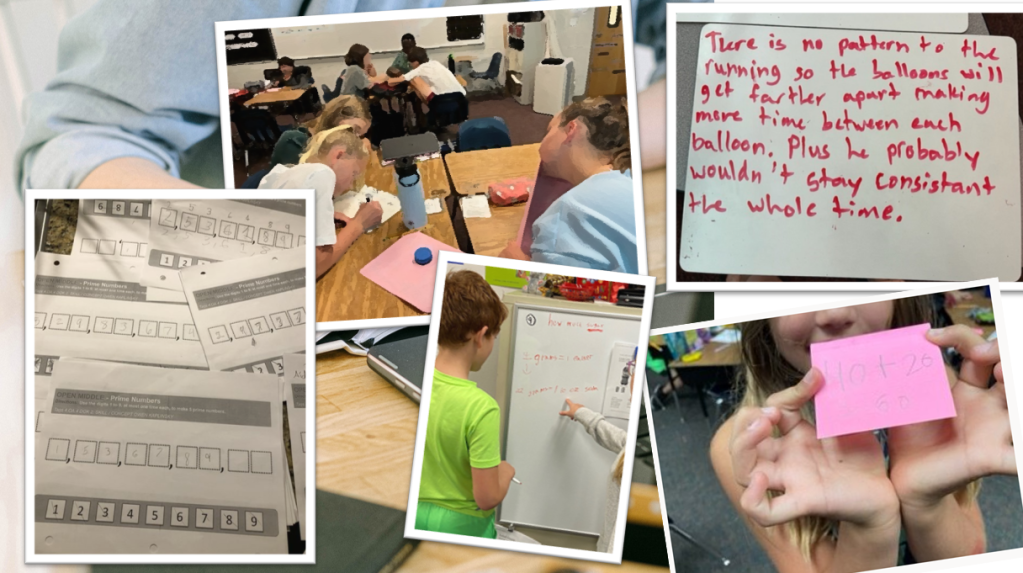

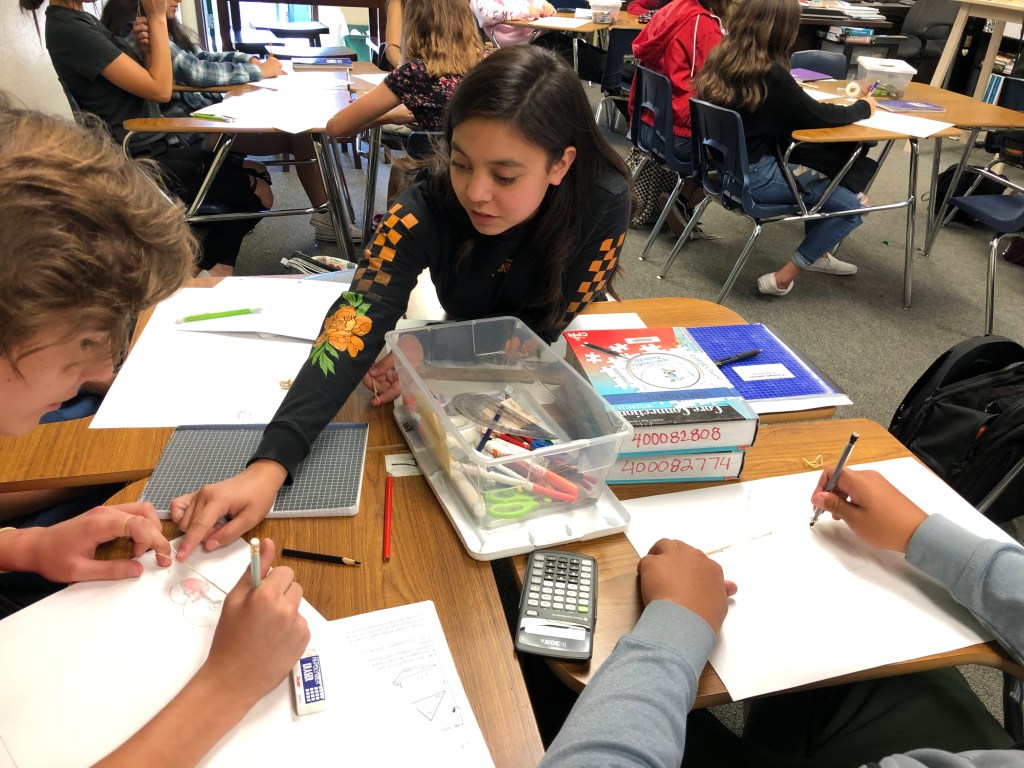

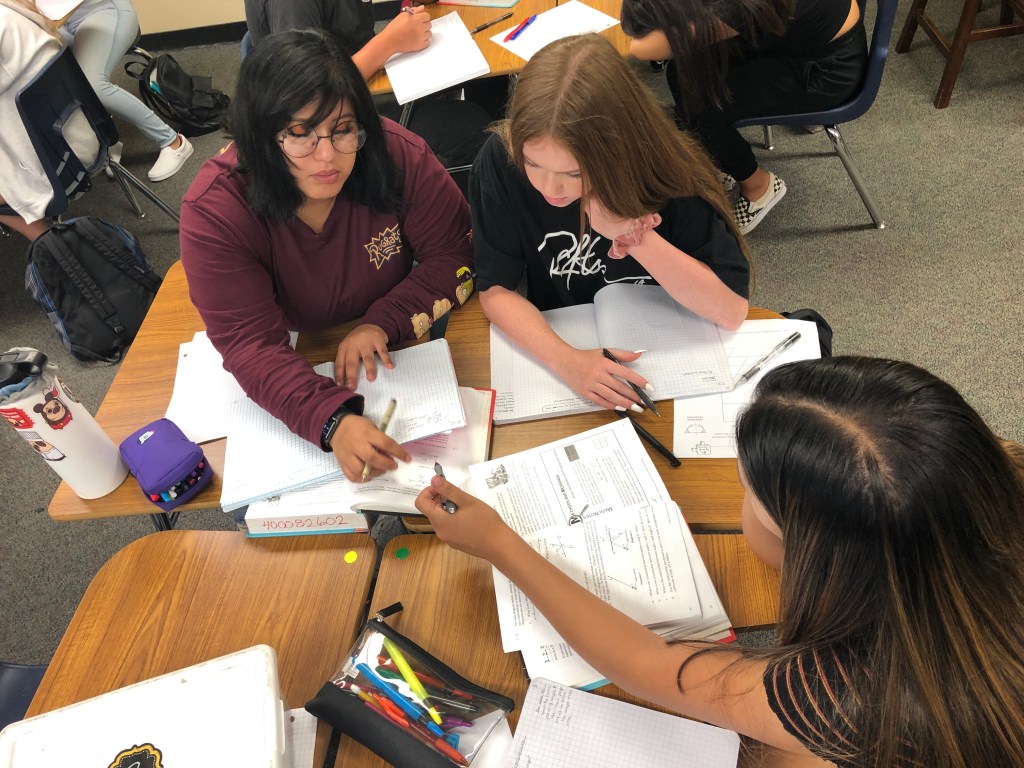

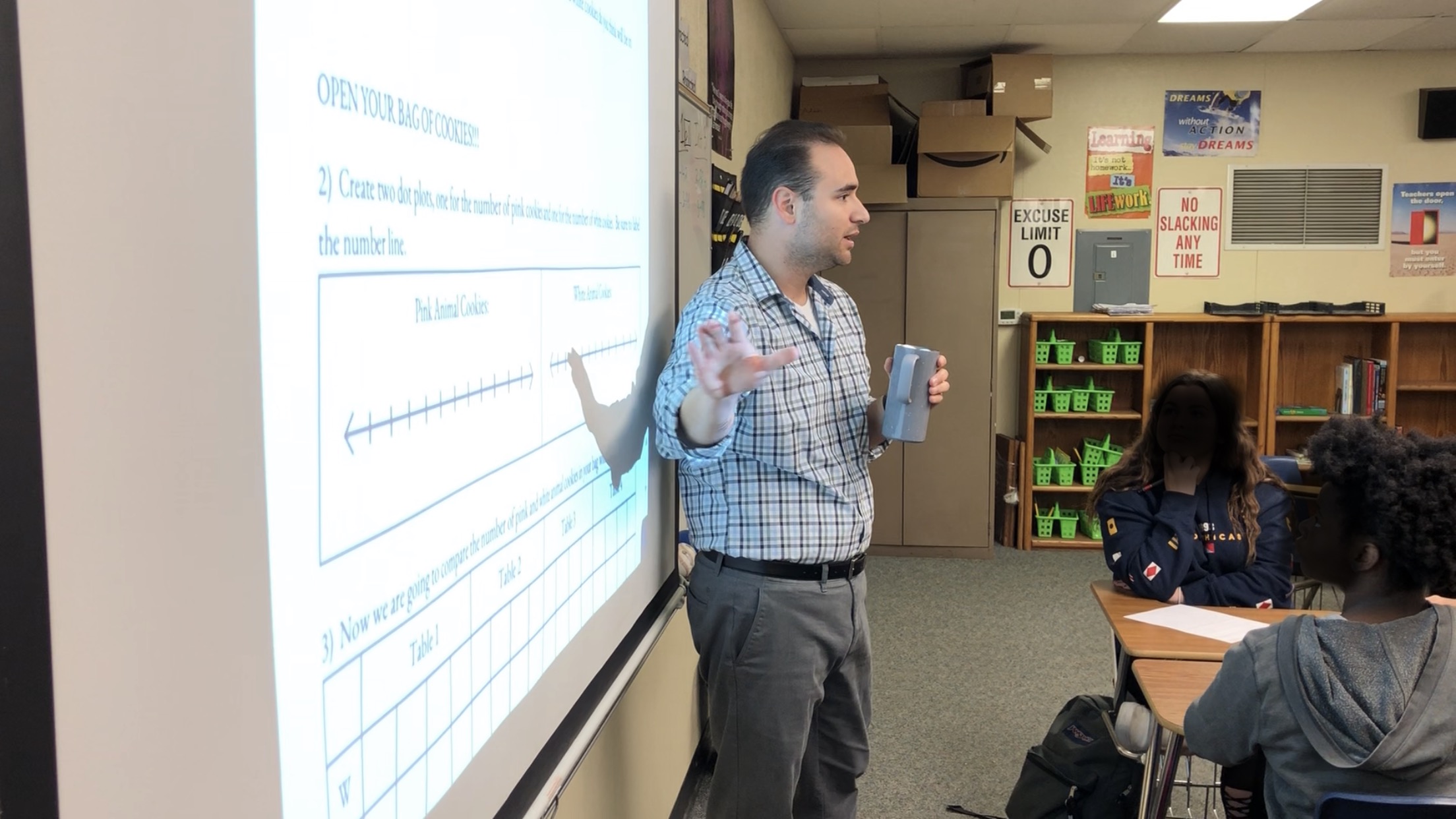

In addition to attendance, teachers also complete a reflection assignment that we called a, “TIY” or “Try it Yourself” for each Math Symposium they attended. We asked teachers to take what they learned and try something with their students. Their assignment included an opportunity to reflect on what went well and what they would do differently next time. We also asked teachers to submit evidence like student work samples, pictures or video of their classrooms, or their detailed lesson plans.

The TIY Assignment

There really were 3 reasons why we asked teachers to complete a TIY assignment:

First, we wanted teachers to take what they learned and try something in hopes that maybe 1 or 2 things “stick.” We were very realistic, from the beginning, that everything a teacher learns over the course of 10 Saturday’s won’t stick

…but if we could get at least 1 thing to stick it would have been worth it. Almost 100 teachers shifting their practice in at least one way–that’s a win in our book.

Second, we needed to hold teachers accountable for the stipend they would be earning. It was an easy way to assess their attendance, what they learned, and how they put it into practice.

Third, having those completed reflections made it real easy to provide evidence of impact to our district leaders and board members—we had teacher written reflections and pictures to share every month!

The Lineup of Speakers

At the start, we asked teachers what they wanted to learn more about and who they wanted to learn from. We got a few suggestions but for the most part we knew we wanted to change hearts and minds around math education in our district so that influenced who we invited. We were so fortunate to have a powerhouse line up of speakers. And honestly, there were so many more that we wanted to invite but we ran out of Saturdays! Trust us, we’re already dreaming about Math Symposium 2.0.

There was definitely a bit of celebrity involved. I mean, our teachers were using Dan Meyer’s Google Sheet of 3-Act Tasks for a while but to have the man himself come work with our teachers was a once in a lifetime experience for some…and the first time some teachers learned about a little thing called Desmos.

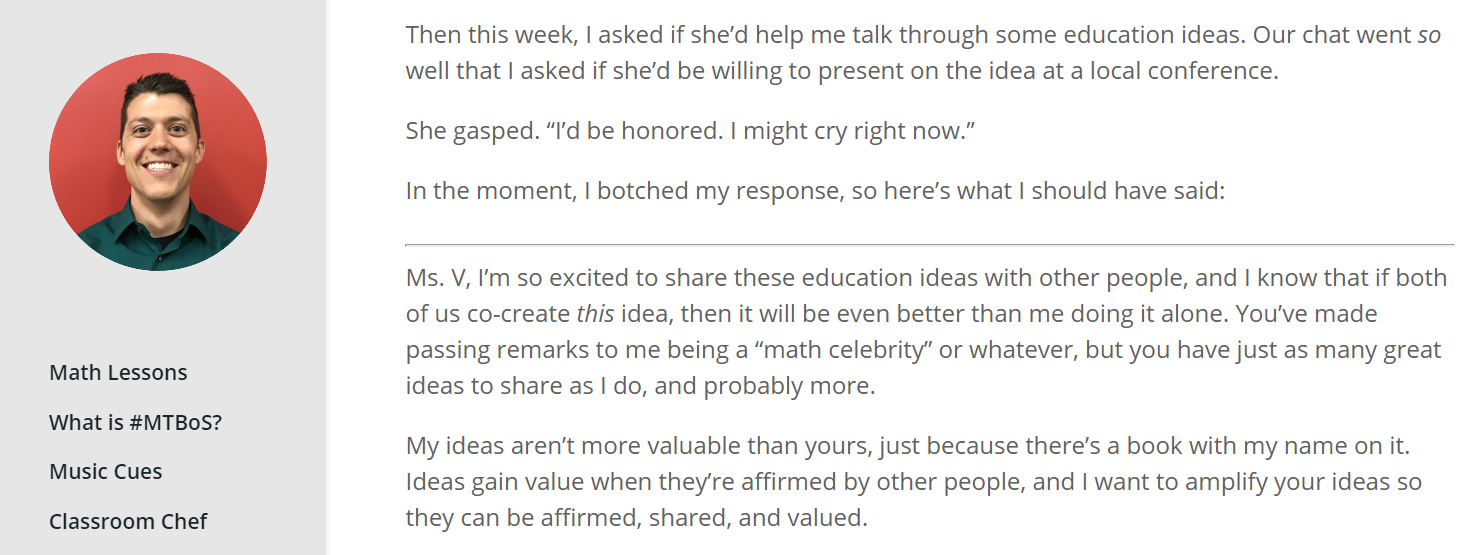

Chris Luzniak came to work with our teachers and as a result invited one of our math coaches to be on his Debate Math podcast! Not only did we get to learn from Chris but now we’re building capacity and expanding horizons for a teacher that might have gone her whole career not learning about Debate Math.

It was so cool when Fawn Nguyen was with us working on visual patterns and learning about rich math tasks. Our teachers have seen Graham Fletcher’s progression videos and know of him. When Fawn mentioned his name, there was an audible gasp in the room when I said, “Graham’s coming in October”!

The most beautiful part of the line up is that each speaker reinforced what previous speakers taught and often alluded to learning that would happen in a future Math Symposium. Teachers are making powerful connections because of consistent and continued opportunities to learn.

Bottom: Chris Luzniak, Dan Meyer, Fawn Nguyen

The Outcomes

When we take a step back and reflect on the impact our Symposium has had on our teachers, we can narrow it down to 3 powerful elements. And don’t worry, a big budget isn’t one of them. We believe, whether you have a big budget or no budget, if Professional Learning contains these 3 elements it will be impactful learning that shifts hearts and minds in the right direction.

First, Professional Learning should have a “Learn-Try-Reflect” structure. It was so powerful that our Symposium was structured so that teachers learned something, then tried it out, and then reflected. We encouraged teachers to be brave and take a risk. In the words of Matt Vaudrey, we made failure cheap.

Second, Professional Learning is more impactful when teachers are inspired to transfer the knowledge to others. We created this excitement around learning that made it feel a little exclusive. Remember how we originally said we only wanted 1 per building? The exclusive feeling has led to teachers wanting to share what they learned because they know they were the “only one” from their building that could come. A highlight for Dr. Bub has been walking into buildings and seeing an entire PLC incorporating the same instructional strategies that one teacher learned from Math Symposium.

Moreover, teachers often only work with teachers in their building (or within their own PLCs) and this created the opportunity to collaborate with teachers from different schools.

Third, create focused and frequent Professional Learning opportunities. Districts are often accused of having too many initiatives which cause teachers to feel pulled in different directions. All the ideas are great ideas but it feels unfocused and overwhelming. Revisiting learning regularly throughout the year and adding on keeps the learning alive and can create a lasting impact. It’s not a new initiative or one more thing. It’s spiraled and scaffolded.

We realized we had built something special when teachers returned, month after month, not only learning more but reinforcing what they had already learned. This focus allowed teachers to make powerful connections with their learning each month.

The Impact

We have seen a difference in our teachers as a result of our Math Symposium and the support of our Superintendent, district leaders, and school board. We used to think of school as reading, writing, spelling…and math. Math is now included. Math is a priority for the whole district and that’s helped the culture to shift. And everyone is talking about it–teachers, building leaders, district leaders.

How can you build a culture of learning?

We were so blessed with the opportunity to create the West Ada Math Symposium and my hope is to encourage you to build something that builds a culture of learning among math teachers around you.

Lead a book study that includes a schedule with follow up meetings and discussions. Create opportunities for teachers to apply their learning, share with others, and reflect on their practice.

Send teachers to a math conference and create an opportunity to share, apply, and reflect. Encourage teachers to be brave and take a risk in their classrooms! Make failure cheap!

Invite one keynote speaker to work with your teachers. They’re more affordable than you probably think and you can never duplicate the inspiration and excitement that naturally comes from a guest speaker! Then, ask that speaker to connect with teachers a few times during the school year to extend the learning. Every speaker we have invited to our Math Symposium were more than willing to connect and extend the learning.

We reflect back on why teachers initially signed up and what things they asked to learn about. Teachers really didn’t know what they didn’t know. That conversation has changed. Teachers are now equipped with promising practices in math education, finding ways to incorporate them in their teaching, and inspiring others!

The ship is moving.

Stay tuned for Math Symposium 2.0!

-PV

PS–None of this could have been possible without my amazing team of Math Coaches. We’ve been told by many that West Ada is the gold standard in hospitality, logistics, and efficiency. And it’s all because of them. Thank you Amanda, Kip, Sarah, and Tricia.

PSS–To all of our speakers that flew to Idaho to work with our teachers. Your time and talent has made a huge impact on learning in our district and we are forever grateful for the hearts and minds you changed. We hope you’ll consider working with us again. Stay tuned for your invite to Math Symposium 2.0!

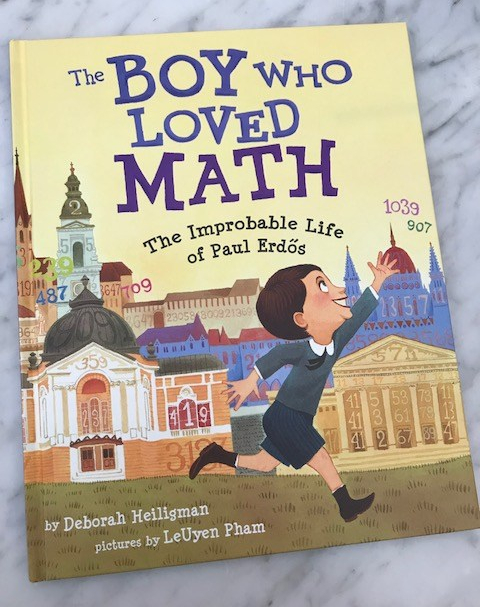

It’s a true story about Paul Erdos, a real mathematician that’s influenced and improved our lives through the math he’s done and shared with others. I love that it brings to light the importance of collaboration. Paul Erdos spent his life traveling around the world working on math with other mathematician

It’s a true story about Paul Erdos, a real mathematician that’s influenced and improved our lives through the math he’s done and shared with others. I love that it brings to light the importance of collaboration. Paul Erdos spent his life traveling around the world working on math with other mathematician